Spring 1919: Ballyizget under the Bolsheviks

By early June of 1919, everything had gone wrong and it was all almost over: across the Russian empire, following the fall of the Romanovs and the gathering ascendancy of the Bolsheviks, not only the White Russian resistance but even the anarchists had mostly been eradicated by the Reds. Those Tsarists with the sense to grab money and jewels, and get out, fled east or south, the lucky ones taking ship from Vladivostok or Ukraine and heading for Shanghai or Paris, or—eventually—the Americas; across the disintegrating empire, the much less numerous anarchists mostly died in the streets of the regional capitols, though a few remnants fought on as mountain and forest partisans, and would do so for the next several years.

It was different in Bassanda, however: in the high alps of the far north, the arid grasslands of the northeast frontier, the wetlands and brackish rivers of the south coast—and in the streets of the capital—the anarchists and indigenous partisans fought on in a four-cornered war against the remaining Tsarist Whites, whose ranks included aristocratic cavalry commanders with little experience of guerrilla warfare or urban combat, and the burgeoning Reds, the Bassandans often making covert alliances between city and countryside which managed to severely constrain the Bolsheviks, whose ranks tended toward politically voluble activists, “journalists,” and factory workers. The guerrilla traditions of the Forest Brethren carried on from the Tsarist era: a blackly-comic proverb of the partisan resistance in this period was: “Whether they’re Austrian or Chinese or Russian, their heads come off just the same way. Except for the Bolsheviks: they just keep talking!”

The hill folk had known the art of ambush for a thousand years. And they knew the rocks and trees, the gullies and hills, the hidden caves and tiny undercut rivulets and overhanging rock falls, out from under which they would creep, in the last hours of the twilight or the gray hours before dawn, striking silently and murderously and melting back into the trees and slipping away over the mountain passes. The time came when the Red soldiers and levies—and even the turncoat Bassandans who had agreed to fight for the Russians, in return for bread and loot—would refuse to leave the fortified villages, knowing that theirs might be yet one more patrol which came back without its horses or weapons or half its numbers, or which did not come back at all.

And in the capitol city, the disintegrating situation was even more fluid—quarter by quarter, sometimes street by street, control and political affiliation wavered and varied, sometimes flipping from one faction to another between one day and the next. Driven by Ivanovich’s ruthless cunning and the Bolshevik terror campaign, the remnants of the Tsarist forces—mostly scared levies from other satellites, pitifully disoriented and under-prepared, “commanded” by unhorsed and overage-in-grade cavalry commanders—pulled back and back, until, by the first of June, they were largely self-isolated behind the walls of the Kremlin castle. Despite their numerical inferiority, and despite the catastrophe of her own capture, Luzja’s partisans had a better picture of the garrison’s morale: domestics, ostlers, and other civilians employed within, some of them actually clandestine members of Lapin’s Cell #1, brought word of disorganization, mistrust, and increasing dispute about whether to abandon the castle entirely—a fearful confusion that was only exacerbated by the Bolsheviks’ cunning and ruthless terror attacks, themselves inspired in part by Michael’s feral hunting in the period of his madness. Ivanovich’s Reds held the inner ring of the city and were steadily tightening their grip, street by street and house by house, on the university quarter and the Kremlin Square itself.

Under Luzja’s order of battle, even in her absence the anarchist Blacks and the indigenous resistance, led by Emir Basha from the Forest Brethren, had managed to hold the outskirts. Undergunned, with smaller numbers and lacking the flow of Russian arms from the caravans which, despite the Forest Brethren’s and the Basmachi’s desperate attacks, daily arrived into the city under heavy guard, the indigenous forces found themselves reduced to bandit raids and back-alley ambushes, never able to break through the ring of outward-facing steel with which Ivanovich protected his forces as they themselves besieged the Whites trapped in the Kremlin. It was a race against time to see which cohort would succeed in investing the castle and capturing its command-and-control apparatus, but the sheer flow of materiel, the sheer implacability of Ivanovich’s greater forces, posed a formidable and, it was feared, impregnable opponent.

**

Until one morning, very early, when a chambermaid who had been assaulted by one of the senior Tsarist officers—a known drunkard and serial rapist who was widely hated by the women of the garrison—reported that long-awaited Imperial orders, several times misdirected or lost with ambushed couriers, had finally arrived from Petrograd, confirming permission for the garrison to withdraw entirely from the capitol city and begin a fighting retreat northwestward toward home. This was reported to have triggered even more furious debate—by this time, almost all military discipline had broken down, as the garrison was devolved into a collection of simpletons, frightened boys, and incipient brigands—evenly divided between that terrified contingent who thought only of escape, and another reluctant to leave, mostly consisting of those who recognized the deadly threat of the secret rage in the countryside through which such a retreat would have to travel.

On the city outskirts, beyond the bristling steel of Ivanovich’s double-ring of besiegers, Michael was called to an emergency council consisting of the Team, now reduced to just Jamshid, Dara, and Yezget, the Lady Professor Lapin, the Forest Brethren, the leadership of Cell #1, and the ragtag representatives of various unaffiliated resistance groups who held individual quarters or squares or isolated back alleys. In the end, after hours of debate which called for every bit of Cecile’s linguistic eloquence and deep history as a scion of Bassandan independence, Luzja hammered out a rough tactical plan and order of battle, though Michael was unconvinced that this ragged coalition could even manage its timetable, much less achieve success. Not for the first time, they felt the excruciating absence of the Sergeant, whose commando-trained tactical genius and combat leadership, and sheer larger-than-life personality, left a catastrophic gap.

But they knew that there was simply no more time. The chambermaid, her torn blouse in rags around her shoulders, her face and eyes aflame, insisted that the Tsarist plans had coalesced around a clandestine withdrawal the next night, leaving behind a skeleton garrison to show lights upon the walls, clattering noises behind them, to provide cover for the majority’s withdrawal. Yezget’s far-seeing grandmother, in turn, insisted that Luzja was still alive, though tight-lipped on the question of whether she was being tortured.

They knew without doubt that time was running out.

What was not known was the proposed fate of the prisoners, though Dara suspected the worst. In the council, she insisted, “They’ll kill them. They’ll kill Luzja. They’ll kill them all. Why would they burden themselves with the care or feeding or guarding of a bunch of prisoners broken down by fear and hunger? What good would it do them?”

The Cell #1 leader said, “maybe as hostages?” but Dara scoffed, and cut across the other’s speech.

“Fuck that. Even those stupid Cossacks know they’re not going to be able to talk their way across the countryside on their road northwest. Me and my team came in that way, and after what we’ve seen, those Ruski bastards should be worried about their own hides nailed onto barn doors. No hostages are going to save them from that.”

There was a silence. Michael looked from Dara’s fierce face, to Jamshid’s mournfulness, to the circle of other leaders around the big table, and then finally at the Lady Professor; no other than Lapin better understood the stakes of standing against the Russians.

Her gaze was abstracted; atypically, she might almost have sat unhearing to these councils of desperation. But at least one of her companions—perhaps Yezget, the ethnographer and historian, perhaps Dara, who had know her before—knew that her inward aspect was not disinterest, but memory: memory that reached back over a decade into her own history, and that of Bassanda. Knowledge of other Tsarist attempts at conquest. Sorrow at the old losses that had been abstracted from the little peoples, the little countries and satellites. But all of her companions believed in her wisdom, and prayed for her direction. And so they sat and waited.

She gazed into the middle distance, her interlinked hands palm-up in her lap as she sat cross-legged in a battered wooden kitchen chair, discarded by some former tenant in this underground chamber. She did not speak, but her lips moved, as if she were reciting old texts. Or perhaps—given the intermittent pauses, when she would break off her silent speech and cock her head, seeming to be listening—perhaps she was holding discourse with some wisdom or memory beyond these cellar walls.

Finally, she sighed, uncrossed her legs, and sat upright, placing her palms upon her knees. Her eyes came back to the present, and she looked from one of the team to another, one by one.

To Yezget she said: “I know this is not your world, my son: I know that you are at home in the halls of learning and the libraries. But unless we fight, in this world now, your world disappears entirely.” Unexpectedly, she stood, and stooped over him, and kissed him gently on the lips. “I believe in your fighting spirit, Yezget.”

To Dara she said: “You know what is to be done, baby sister. But this time, let us do what needs to be done—even, if we must, let us kill—without rage. Let the rage depart. Let us take action, and if necessary, let us kill—but only in order to prevent worse suffering.”

Lapin turned to Jamshid, who sat, eyes downcast, staring at the Sergeant’s big Webley revolver, which lay in his lap across his cupped palms. To him Lapin said nothing, but simply stepped close to him and, after a moment, took his head in her arms, cradling it against her bosom. Jamshid began to cry; he made no sound, but the tears welled up and wetted her blouse. Lapin leaned down and whispered into his hair: “Fight for him, Jamshid. He loved you; fight for him. Fight, in order that his death can have meaning.”

**

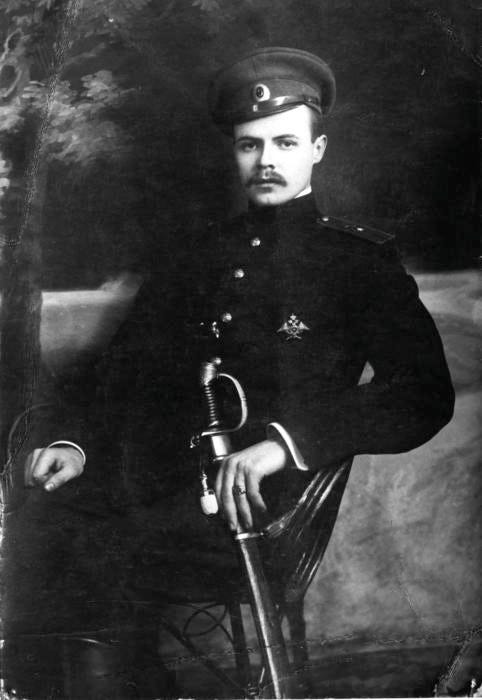

The Russian cavalry major in the Kremlin garrison was more than worried: he was convinced, with a nearly complete fatalism, that both he and his command were doomed. Unlike the fat old buffers in the mess—under the smoking guttering torch-lit illuminations of this backwater smelly medieval castle—the major understood just how dire his situation, and that of his troops, actually was. He had watched as the country outposts had been burned-out, overrun, or abandoned, their troopers killed, deserted, or simply disappeared under the earth or into the mountain crevasses; His Imperial Majesty’s forces steadily retreating from the country to the garrisons dotted around the capitol; then, burned in their beds or murdered in the back alleys, the survivors falling back on the walled Old Quarter of the city; then, nearly starving as they ransacked the medieval houses to find cupboards bare and even the chickens and pigs driven off or consumed, within the walls of the Kremlin palace itself. The major had so far managed to avoid mutiny, direct refusal of orders, from the troops under his command, but he estimated that within the next 24 to 36 hours of stress—or less, if the wrong orders were given—he would face open defiance. And the major saw no sustainable outcomes from any such orders, so he sought to avoid any awkward circumstances in which he might publicly be instructed to issue them.

He was pacing the walls, on this warm June night, checking on the attention of his sentries. It might be that they would indeed fall back from the castle and attempt a fighting retreat north, though the Major had his doubts about any such journey’s logistical feasibility in the best of times, and with full mobile support, but he was determined that, as long as he commanded a detachment of the garrison, no errors would be made on his watch. He paused in the shadow of an embrasure to light a cigarette, cupping the match in his hand to conceal any light, bending over to draw the harsh smoke of the cheap mahorka deep into his lungs.

Unexpectedly, he heard footsteps, quite open and unstealthy, clambering up the stone staircase from the parade ground below. He turned his head sharply to see the figure of a tall, wide-hipped woman climbing into view. Her hair was piled high on her head, and in the dim starlight he could see her dark overcoat thrown back from her shoulders; the deep V of the dark blouse under the coat framed the white skin of her throat and breasts. She smiled and said, in heavily-accented Russian, “Got another smoke, soldier?” The major smiled in turn—this was an unexpected and most pleasant interruption to his fretful strategic brooding. He shook another cigarette from the pack and offered it to the woman: she took it and placed it between her lips, as he struck another match. The woman leaned forward, the dark blouse falling further open, and clasped the hand holding the match to bring it to her mouth, looking up from under long eyelashes at the major as she inhaled deeply.

He heard a scuffling sound against the stone of the embrasure’s outer wall, but even as he straightened sharply, the woman’s two hands clamped over his own, pulling down hard. Already falling forward, the major wrenched his head around to see a tall thin figure, dressed in dark clothes and with a balaclava pulled over its head, slide like an eel over the embrasure, thumping to its feet almost directly in front of him. He caught a momentary glimpse of bespectacled eyes, eerily reflecting the dim starlight in great grey luminescent disks like goggles, blazing in the dim light from the courtyard over the black wool of the balaclava, but before he could even cry out, the woman shot her hand up between them, jamming her fingers like a gag into his gaping mouth. He gasped—no sound louder, and a knife slid home between his ribs from behind. He died with the cry in his throat, and he coughed a torrent of blood over the woman’s fingers and down her arm.

Yezget caught the major as he fell backwards, and eased the lifeless body to the catwalk on the wall. He nodded wordlessly to the woman, who wiped her blade on the coat, threw it off her shoulders and turned to look down into the parade ground, waving her burning cigarette in a triangular pattern.

**

Looking up, Dara saw the faint spark of the cigarette, on the Kremlin battlements above, describing a triangle in the darkness. She looked over her shoulder, hissed for attention, and inclined her head sharply toward the sentry gate a short distance across the square. Jamshid nodded and took up a position at the corner with her, bracing his shoulder against the rough stone and aiming his carbine, just over her head, at the target door. With his free hand he slapped her shoulder, and without hesitation or a word spoken, she ran, crouching nearly double, the dozen steps across the moonlit square, into the ink-black shadow within the door’s deep mullioned arch. She froze in the doorway, and looked back. Keeping his carbine braced, but raising his head from the sights, Jamshid craned his neck to scan the silent storefronts that circled the square; seeing nothing, he snapped a thumbs-up and then tucked his cheek into the carbine’s stock again, sighting on the door just past Dara.

**

Outside the walls, across the Square from the Kremlin castle, Michael gestured sharply to the basmachi clustered behind him under the arch of the cathedral. Though unhorsed, and penned within the walls of a medieval city instead of riding free on the steppes, Luzja’s troopers had proven themselves to be remarkably adaptable as urban guerrillas, with both a native and a learned ability to move silently and swiftly, and an unbridled zest for close-quarters fighting against the hereditary enemy. Their leader, Rustum, was particularly adept at following the hand commands which was the only language he shared with Michael, and he showed a remarkable capacity for tactical focus in active-fire situations—in all, a natural infantry squad leader, even in the absence of his beloved horses. Michael looked over his shoulder and saw Rustum’s pale eyes against his dark face, reflected in the moonlight that spilled into the silent Square. He pointed left and right, diagonally across two tangents to the corners of the Square on either side of the Kremlin’s facade, and, extending a thumb and forefinger, inverted the thumb to point straight downward: “enemy in sight.” Rustum leaned back to his troopers crouched behind him, and whispered a single sentence in the northern dialect. Several of the troopers grinned, shifting their weight, their teeth white in the darkness, and then slipping in two files past him. Michael looked an interrogative, and Rustum nodded vigorously, giving a thumbs-up. Michael resettled his sights on the sentry tower above the main gate.

**

Below the castle walls, somewhere in vicinity of the subterranean cells, Dara, clad in black, slipped along the rough stone walls of the corridor. She was trying to carry the complex three-dimensional drawing of the building in her mind’s eye, but her rage at the news of Luzja’s torture, and her fear that their rescue might be too late, continually clouded her vision with red shadows. She peered around the next stone corner and saw, forty or fifty feet ahead, under a dim electric light, the faint backlit outline of the sentry she had been warned the Cell #1 informants had warned her to expect. Her mind cleared in that moment, and for the next few seconds, she moved almost purely on learned instinct, with a balletic economy of motion. Sliding back around the corner out of sight, she gestured with a clenched fist to Jamshid and their strike team, crouching a line along the wall beyond him. She slipped her carbine off her back and set it gently and silently, butt down, leaning against the stone wall. Then she slid her thin-bladed kindjal from its wrist sheath, gestured with a wide-outspread left hand for Jamshid to cover her, and slipped around the corner again, Jamshid on her heels, with his rifle up. Without hesitating, Dara moved like a small, dark, flitting shadow, hugging the wall, down the corridor toward the sentry. Six feet away, she slowed to a halt, listening, all senses alert to other noise: there was none. Silently, poised on her toes, she raised her left hand, clearly silhouetted from Jamshid’s vantage against the dim light beyond her, and waved it gently up and down twice. Keeping the rifle’s stock clamped against his cheek with his right hand, and still zeroed-in on the sentry, Jamshid gently flipped a small pebble in an arc down the corridor, to land several feet beyond the sentry. Its rattle was loud in the stillness, and the startled sentry jerked to attention, bringing his rifle up.

He was half crouched, the rifle half raised, peering down the dim corridor in the wrong direction, when Dara landed on his back like a small black cat. She clapped a hand over the guard’s mouth, jerked his chin to the left, and drove the kindjal downward, just inside the clavicle, slanting down into the heart. A single harsh grunt, a scrabbling of feet on the dusty limestone of the corridor, and the guard collapsed. Dara eased the limp body to the floor, and even as she did so, Jamshid, running silently and fast, hurdled the dead sentry and ducked through the half-ajar door.

There was a sudden, isolated rattle of small arms fire from outside and above.

**

Up in the shadows of the parade ground inside the walls, Rustum did not even turn his head, despite the firing’s proximity—it was the expected diversion. Searchlights stabbed downward into the Kremlin Square, but, pointing in the wrong direction, they found nothing. Sentries scurried along the walls, peering into the darkness below, as if—irrationally—they would see better in the aftermath of the blinding arc lights, but there was no further sound. Rustum stooped to peer at the old iron padlock that sealed the large double doors to the motor pool, and looked a question to the teenaged girl, clad in a mechanical boffin’s dirty coverall, who stood behind him, barely coming up to his chest. She ducked forward under his arm, glanced at the lock, and brought out a small zippered handbag of tools. Hunched over, the lock obscured by her back and her bent tousled short hair, she worked for a few moments, and then grunted with satisfaction. She looked over her shoulder at Rustum, grinned cockily, and, still grinning, twisted her wrist. There was a soft snap and the padlock fell open. He grinned back, slapped the girl on the shoulder, and they and the troopers passed inside. The girl went immediately to the big armored car that loomed like a rhinoceros over all the other vehicles in the yard, and wriggled like a salamander under its low-slung armor plating.

**

Jamshid stood frozen, just inside the unmarked door of the high-arched subterranean room, incongruously lit with powerful electric lights suspended from the high ceiling. Perhaps, with its lowered floor down a few steps from the doorway arch, and the big open ovens built into its walls, with their tall stone chimneys reaching up toward the outside, it had originally been the castle’s kitchens or bake-house. But now it appeared to have been put to a darker purpose: spaced with military precision across the stone floor, with its old iron gutters and drains for washing down the kitchen at the end of the day’s cooking, were a series of high-posted iron bedsteads, their legs bolted to iron fixtures set into the stone itself. There were leather straps and steel clamps riveted to the bedsteads, and at the head of each was a tall wooden tool-rack. Except that what the racks stored, in serried ranks, each neatly aligned with its paired hospital bed, were not tools.

Moving like a sleepwalker, Jamshid stepped down into the erstwhile kitchen. As if in a dream, as if he could not feel his feet on the rough stone of the floor, he paced between the tables, turning his head to peer distractedly at the wickedly-shaped instruments, none of which he recognized but all of which exuded the form-following-function of tearing flesh and minds. Having crossed the far end of the room, he came to a halt, his mind stunned and refusing to process the evidence of his eyes.

Dara appeared, panting, in the archway from the corridor. She was roughly scrubbing the blood over her kindjal, and—absorbed in the act of sliding it home into its wrist sheath—she called out before she had looked clearly into the room. “Jam’? Jam’, quick, we have to keep moving…” Then she looked up and across the room and saw Jamshid down and below, now halted and stock-still among the beds. With dawning horror, she realized that these were the torture chambers.

Jamshid stood across the room, at the last rank of beds, each, like all the others, bolted to the floor and outfitted with an array of clamps and straps to immobilize flailing limbs, each with its rack of instruments of pain neatly arrayed at its head. But Dara realized that the last rank of beds was somehow at the same time different, for those last beds were all of more modest dimensions, only three or four feet in length, unable to accommodate a full-grown person’s frame…

Jamshid spoke, his faint voice coming clearly across the room in the stunned silence.

“Dar…?”

With supernatural acuity—as if rage were enhancing her eyesight beyond normal capacities—Dara saw that there were tears running down Jamshid’s face.

He held up his hand. He was holding a child’s stuffed animal.

Outside and far above, there was a distant rumble of artillery.

**

Michael and his strike force, now past the dead sentries and just inside the Kremlin’s defenses, heard the artillery as a proximate roar, just outside the walls, and instantly identified its tactical implications: Ivanovich’s besiegers were driving home the final assault.

**

On the walls, Yezget heard that roar and—though an amateur at war, and thus unable to identify the ordinance—he knew that noise was an enemy, and no part of Luzja’s original plan, and he froze for a moment. Rustum snapped an imperative question, and Yezget shook himself, saying, “Yes, yes, of course—the next step.” They hurried down the open staircase that led to the parade ground, and at its foot were joined by the tall woman who had distracted the hapless Russian major, now dead on the catwalk above: she had a pistol in her hand, a black sash tied around her upper arm, and more women similarly armed behind her. Without hesitating, she turned and led the combined party, at a run, for the servant’s entrance to the barracks.

**

In the hills, at the very edge of the forest belt north of the city, Ranbir Singh heard the faint rumble of big guns and clapped his night glasses to his eyes. There was artillery fire in a semicircle around the Kremlin castle, the guns’ flashes reflected upward by the building-lined streets and lighting the loud clouds over the old quarter, and, inside the parade ground over whose barrier walls he could just see from his higher vantage point, scattered pinpoints of small-arms fire—the strike teams were at work.

He turned and gestured, and a serried rank of basmachi horsemen came out of the trees, ranging themselves to each side and looking downward with him toward the besieged city. There were ragged partisan infantry behind them.

**

A few blocks from the Kremlin Square, in an old side street of artisans’ shops—shoemakers, saddlers, watchmakers, clothiers, and the like—a young blacksmith sat in the firelight of the small cottage that faced the street, his wife sewing, bending close to the small lamp on the mantle piece. At the rumble of artillery, both raised their heads. They made eye contact, and with no words spoken, the blacksmith vanished into the small deeply-shadowed shop behind the cottage, emerging a few seconds later with a hammer in one hand and a pistol in the other. His wife, hurrying three small, nightshirt-clad children down the steps of a small storm cellar in the stable yard, paused on the second step; he bent and kissed her. Then the cellar’s door banged shut and the blacksmith moved quickly along the carriage lane beside the house to slip out into the street. Hammer in hand, he set out at a run toward the Kremlin.

**

In a small dimly-lit illicit tavern—really hardly more than a dry cellar, with rough wooden chairs, half barrels as tables, and a stink of cabbage and beer—a group of young men ceased their boisterous banter. The eldest stood and turned to look at the publican, an older man with a waxed walrus mustache and a big belly, who stood still, head cocked and eyes defocused as he listened. The young man said quickly, “Well, baba??” The old man listened for a moment more, then his eyes focused and he looked sharply at the young man. “Yes: big guns. Go now.” The young man turned to his companions and the group left quickly, jostling and clattering up the cellar’s wooden steps to the street. Behind them, the publican reached under the bar and withdrew a worn shotgun, its stock and barrels cut short. Thoughtfully, he thumbed back both hammers to visually confirm the shells within. Then he eased the hammers back down again, carefully turned down the lamps to prevent any risk of a fire, and followed.

**

A few hundred meters away, in a small, well-appointed two-story house that abutted the university’s Baroque-styled humanities building, a widowed university professor sat in his second floor study, a lamp burning, multiple books stacked open or face-down on the large cluttered library table, with his head in his hands, massaging his temples, a virtual icon for writerly reflection. The crackle of small-arms fire just on the other side of the square, where the rear walls of the Kremlin formed the tall rear wall of the university grounds, brought his head up, and he cocked an ear to listen closely. Then he stood, with sudden decision, and stepped to a closet behind the desk. Groping inside, he fished out an ancient officer’s Sam Browne belt and holstered service pistol, belted it on, and headed for the study door. Then, as if at an afterthought, he stopped at the library table, poured a hefty portion of brandy into a snifter, and tossed it off at a gulp. With a sharp exhale, he turned and left the room, as the sound of artillery grew.

**

In a deep window-well at the side of the cathedral, from beneath which blew up warm air from the cathedral’s big coal furnaces, three street children, perhaps fourteen or fifteen years of age, huddled for warmth, passing a hand-rolled cigarette from hand to hand. The first crackle of small-arms fire brought them out of the window-well like frightened forest animals, but at the rumble of artillery, the tallest child—a skinny girl with short-chopped henna’d hair—turned to her companions, her face hard, and gestured fiercely for them to follow. As they moved, she stooped to pick up a pair of loose cobblestones.

**

Dara’s team had found the guard room that serviced the cells and the torture chamber. Moving like shadows, they had captured the senior guard sergeant, still with a blood-splashed apron over his ill-fitting uniform, and pinned him spread-eagled on the floor; four of the basmachi knelt hard on each of his four limbs, and Dara had stuffed a leather glove deep into his mouth to silence him. Nevertheless, he grunted and struggled until Dara drew the kukri, held it before his eyes, and then laid it next to his left eye.

“Shut the fuck up, Cossack, or I’ll take both ears and you won’t be able to hear me tell you that anymore.”

The sergeant subsided, but glared furiously and grunted furiously through the gagging leather. Dara ignored him and looked up, as Jamshid appeared panting in the guard-room door.

“Nothing. They’re not here. We found Luzja’s kit, but she and any other prisoners are gone.”

Dara leaned down to glare into the guard sergeant’s eyes.

“Where are your prisoners, you cunt?”

The sergeant glared back but made no sound. Dara’s expression did not change, but the razor-sharp kukri flicked three inches, and the sergeant screamed with pain behind the leather gag, writhing against the pinioning basmachi; the stump of his left ear was spouting blood. Dara held the leaf-bladed kurki, now smeared with the sergeant’s blood, in front of his eyes; in her other was his severed ear. Then she laid the cold steel blade alongside the Russian’s nose, and reached forward to pluck out the improvised leather gag; the Russian was gasping and panting with pain, though otherwise—now—too terrified to move.

Dara spoke again, her hot black eyes locked on the guard sergeant’s, which were now blinking back tears. “Last chance, Ruski. Give me the right information, or I’ll take your nose. And then your other ear. And then I’ll take your balls, and then your eyes.”

The sergeant gasped “No! No, I’ll tell you. Colonel Ivanovich took the partisan woman to the roof—I swear!”

Dara leaned hard on the kukri and now a trickle of blood from the Russian’s nose ran over the blade.

“What was that name, you torturing bitch? Which ‘Colonel’?”

The sergeant babbled, “The Russian! The one with the Bolsheviks! He said he was actually a loyal subject of the Tsar, working for us—that he would help us escape the siege! I swear!”

Dara was shocked into silence. Ivanovich? The newly-hatched Bolshevik, the ex-Tsarist colonel who had so brilliantly designed the siege against the Russians in the Kremlin Palace. Ivanovich?

In a fierce frantic whisper, Jamshid put her questions into sound: “Who the hell is he? How many different ways does the bastard’s treachery run?”

Dara shook her head to clear it, and jumped to her feet. “No time now. Whoever he is, whatever his allegiances, he’s got Luzja.”

She flicked a hand toward the guard sergeant, and snapped to the basmachi “Bind him and bring him! We have to get to the roof!”

And she and Jamshid left the guard room at a dead run.

**

The young blacksmith, who had often worked on the garrison’s horses in the castle itself, slipped into the stables through a set of double doors, just big enough to admit a two-horse shay from the street outside. Moving quickly and quietly through the darkness of the familiar space, needing no illumination in order to elude the anvil, racks, forge, and water-butt, he flattened himself against the great doors that stood half ajar—though it did not occur to him to wonder why—in order to peer out, pistol half-raised in his left hand, into the moonlit parade ground. The artillery continued.

Behind him, from the darkness of the stables, he heard the click of a pistol’s hammer being drawn back. He froze, and then a polite, rather cultured, young man’s voice said, “Good evening, sir. I see you have a hammer. I wonder if you might care to lend assistance with a recalcitrant lock on a door, near the main gate?”

**

The three young men, still half-drunk from the tavern, were in a side-alley, trying to stand upon one another’s shoulders in order to reach a window in the Castle’s outer wall which was twelve feet off the ground. Cursing and arguing, they had twice managed to build a pyramid of one upon another’s shoulders, but each time the third, the youngest and lightest, tried to clamber up his fellows’ bodies, kneeling on the topmost set of shoulders, kneeing his partner’s face or ear, abrading their shoulders with his boot souls, and perilously scrabbling upward, straining to reach the window sill, he slipped, or his supporters tottered and swayed, and he fell down or entirely off their human ladder.

On the third essay, the third youth, the youngest and lightest, had finally managed to clamp one hand’s fingers over the window’s sill, in the few inches that had been left open to the night air, though he was not at all sure that he could chin himself up and in to the window. The point became moot, however, when the window when up with a bang, and a deep voice said within, in the northern dialect and accent, “What do you boys think you’re doing?” The bottom two youths instantly fell in a heap, leaving the youngest dangling, whimpering, by one hand in agony from the windowsill. A tall figure with a shock of curly hair leaned over the sill, aiming a carbine straight down at the two on the ground; the click of the hammer being pulled back was even to make the youngest youth lose his hand grip and fall in a heap on top of his comrades. The curly-headed figure was taking aim straight down, when another voice spoke, in the same dialect and accent from the shadows on the ground across the alley. The curly-headed defender called a sharp question, and incongruously the man in the shadows laughed aloud, that laugh matched from within the dark window.

The bartender from the tavern, his sawed-off shotgun held casually now across his shoulder, strode across the alley and slapped the biggest of the youths on the top of his head.

“Get up, idiot, those are friends inside.”

He turned and whistled up to the window. A moment later, a rolled-up rope ladder was tilted over the sill, unspooling as it fell down the wall, and then hanging jerking and dancing just above the street. Curly-headed Emir Basha, with his carbine leaned out of the window and said sharply, in Russian, “get up this ladder, you dopes, if you want to lend a hand before it’s all over.”

The biggest of the youths looked around at his fellows, as if expecting someone else to take the lead, and then—belatedly—laid his hand upon the rope ladder and began to climb.

**

The university professor, bitterly missing the tangible authority conferred by his old uniform, and at a bit of a loss for how to proceed, reacted as an academic administrator might have been expected; controlling his limp against the uneven cobbles of the approach to the Kremlin gates, he strode up the center of the road to the postern door. For a moment he hesitated: no guards were visible, and no lights, and there was none of the accustomed sound of movement and labor and conversation within, beyond the door. He leaned far back, craning his neck to look upward at the battlements overhead, and then to each side: still nothing. He turned and looked out at the deserted Kremlin Square, with its statuary, grand sweep of cobble, and iron bollards with stout black chain between them. There was no sign of movement, and, even as he looked, the sound of artillery abruptly died, like the roar of a waterfall turned off like a faucet. In the echoing silence, he turned to look back at the postern. He was just—feeling faintly absurd—raising his clenched fist to knock, like a tinker at a farmhouse’s back door, when the postern swung silently inward toward the parade ground. The professor hesitated and then stepped through the door into the parade ground, to be confronted, from a few feet away, by a tall thin figure wearing a black balaclava, with spectacles that glittered in the moonlight as if frosted, and a carbine in its hands. Behind the figure and now, the professor belatedly realized, surrounding him, were several women in street clothes, their hair bound back, training weapons directly at him.

He gave a startled exclamation, before the tall thin figure spoke, in a casual, ironical tone.

“Good evening, professor. Would you care to take part, once more, in a revolution?”

The postern door closed.

**

The party of street urchins, led by the tall skinny girl with the chopped-off henna’d hair, had crept into the castle via the storm drain they usually employed when stealing food or clothes from the mess or barracks. As they emerged from the tunnel on all fours within the barracks, a tall bulky figure seemed to rise from the floor a few yards away, nearly invisible in the gloom. The youngest of the children, a boy of no more than eight, squeaked with alarm, and there was a general startled and swift motion back toward the tunnel, but the tall girl halted when the big figure spoke, in Bassandan, his voice a bass rumble.

“Do you want to help fight Ruskis, girl—you and your friends?”

The henna-haired girl controlled her desire to flee, pulled herself upright, and glared fiercely back at the giant Rustum. Though she did not speak or otherwise move, he smiled and nodded.

“Good. Take your crew. Scatter and find us Russians, throughout the castle. Then came back and find me, and my friends, and show us where the soldiers are.”

The tall girl nodded abruptly, glanced at her fellows, and indicated the barracks door that led out into the corridors and the complex of buildings beyond. The party of children, flitting like elfin shadows through the gloom, scurried to follow suit.

The big man smiled, uncocked his assault rifle, and followed.

**

In the banqueting hall, with its high-vaulted ceiling, that lay on the top floor of the Kremlin palace, its balcony looking out over the square below, and from which generations of political speeches, manifestos, imperial edicts, and revolutions had been announced or contested, Michael and his basmachi came down the wide-sweeping steps from the great double doors as if entering the lion’s den. Outside, the rolling rumble of the Bolshevik artillery had died away—he did not know what this portended. His personal team swept efficiently down both sides of the hall, kicking open the doors of anterooms and adjoining corridors, confirming that no Russians were left a live threat, posting guards at entrances and egresses.

Michael, however, moved down the center aisle of the hall, under the high-peaked roof, toward the dais where the Tsarist commanders had sat. In the echoing silence after the cessation of the artillery barrage, he was vaguely conscious of his partisans laundering this top floor, the occasional burst of small arms fire. There was no sign of any occupants in the hall itself, but two small doors were behind the dais. In front of one, the tapestry which normally concealed one had been jerked aside as if in haste, and it was open. Michael approached the door cautiously, his carbine raised and his finger on the trigger. The tapestry flapped in a cold wind which seemed to be coursing down from the steep rising staircase behind the door. He looked back into the main hall, and saw Dara and Yezget jogging toward him. They came to a stop, and without a word, Dara shook her head: no sign of Luzja on this floor. Yezget looked a question at Michael, who nodded, pointed to the other staircase, made a circle in the air with a vertical forefinger, and pointed straight overhead. Yezget nodded quickly and gestured to his team sergeant to bring all available personnel into the hall.

And then the three, Dara and Yezget and Michael himself, started up the two steep staircases, east and west, that led toward the roof.