From the Bassanda Dictionary of National Biography

Etxaberri كزافييه le Gwo

Born Galveston Island, 1931.

Though conventionally understood as a place-name (the village of Xabier in the Basque country of northern Spain), another etymology suggests that the name “Xavier” is actually Moorish, from the Arabic Ga'afar meaning "splendid", "bright". In the case of Etxaberri le Gwo, the Arabic derivation becomes more plausible in light of genealogical research which has suggested that his mother’s family was actually 16th century American criolla, descended from Esteban de Dorantes (c1500-39), the Moroccan-born black African who came to New Spain with the Narváez expedition, after prior stops in Hispaniola and Cuba. It is generally accepted that Esteban died in the Zuni Uprising of 1539, but another, possibly romantic school of thought argues that he was not killed; rather, that he and Indio friends faked the death as a means of winning his freedom—and that he lived out his life, fathering an extensive clan, in the New World. Some folklore legends even hold that the dark-faced Zuni Kachina dancer Chakwaina is based on Estevanico.

Etxaberri’s own father was of Caribbean Creole ancestry; he thus inherits the tradition of Barbadian rukatuk acoustic music, and the lineage of the smugglers and privateersmen who shipped out of Barbados during the War of 1812. There are likewise family connections with the communities of pirates and slavers that revolved around Jean Lafitte (1776-1823), who fought at the Battle of New Orleans after settling at Barataria Bay (Louisiana) and Campeche (Texas). Etsy himself was extensively tattooed, which lends credence to the possibility that he may have also had South Seas heritage (one grandfather is said to have come from Rokovoko, the home island of the harpooner Queequeg in Melville’s 1851 Moby Dick). Given his father’s Haitian and Barbadian maritime experience, and the evidence of his Eastern Mediterranean encounters in the very late 1940s, it therefore seems possible that, prior to his European sojourn, Etxaberri might have shipped out to the South Seas as a teenaged deckhand.

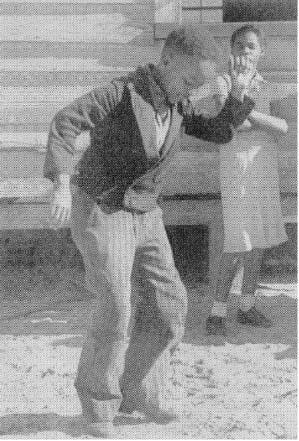

Another branch of his father’s family served as informants for Lydia Parrish in her 1920s Southeast collecting for her publication Slave Songs of the Georgia Sea Islands: the book contains a photo labeled “Snooks dancing ‘Juba’,” which may be an older cousin, around age 6.

Revealing mention of “Etsy” himself comes in a 1947 letter from the New York-based Ukrainian film-maker (Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti) and collector Maya Deren to Yezget Nas1lsinez, whom she had met at Cannes in 1946, while she was in New Orleans just prior to her departure for Haiti. That initial introduction may have come through NOLA’s Caribbean expat community:

“...I also make known to you the young American violinist Etxa le Gwo. He is about nineteen [actually seventeen], from a Haitian Creole family I think [NB: actually Barbadian]. He has extraordinary aptitude for concert music, but surely within him there is also the music that comes from his family lineage.

He is fit and energetic—I went with him on horseback to a family gathering southeast of the City, beyond the paved roads, in the watery Plaquemines Parish, at a place called Bay Tambour, and he is a remarkable horseman. The music played, featuring the unlikely combination of accordion, violin, guitars, percussive triangle, and laundress’s scrub-board, was energetic and infectious.

“He has very little money and I think it unlikely that he would be able to travel to Bassanda without assistance. I leave for Port au Prince within just a few days, but I enclose his mother’s mailing address in Houston Texas. Perhaps there may be a way for you to employ him in the future...”

In the event, despite Deren’s enthusiastic introduction, there is no evidence of immediate correspondence between le Gwo and Bassanda at this time.

What we do know is that he left school at 17 to ship out as deckhand on Caribbean sugar boats, which further explains his familiarity with Haitian vodun, Cuban rhythms, and—especially—Jamaican musics. Not all of his voyages are documented, though his music and accent showed influence from all these island nations. It is inferred that he met both Mississippi Stokes and—possibly—Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, all of whom served in the Merchant Marine, though those circles’ hiring halls in various port cities. He certainly visited the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as the South Pacific, in the late ‘40s; and he is said to have played with the saxophonist Zoya Carutas on shipboard as she was completing her service with the United Service Organizations, just before she met Nas1lsinez in Odessa in early 1949. It seems possible, therefore, that Zoya brokered the re-introduction of le Gwo to Yezget-Bey early in 1950.

An additional reunion was made, with the drummer Részeg Vagyok, when Etsy joined the band—though Vagyok’s Displaced Persons papers were almost certainly forged through Madame Szabo’s contacts in the international Roma underground—and they were first “introduced” in a Ballyizget rehearsal hall in June 1950. At sight, they called one another “Zag” and “Zayv,” and in that first rehearsal it became apparent that they had musical repertoires and even possibly prior experiences in common. Though the following is unsubstantiated, if Vagyok was in fact an American ex-serviceman (see elsewhere in the Correspondence’s personnel files), the two’s shared experience with music of the English-speaking Caribbean might have occurred as members of various South Atlantic maritime communities just after World War II.

The period during which Etxaberri joined the ensemble is conventionally regarded by scholars as marking the historical watershed in which, for both practical and formal purposes, the ad hoc “People’s Liberation Orchestra” morphed into the Bassanda National Symphony Orchestra. During these years, the war-time chamber group (Nas1lsinez, Szabo, Thorvaldur Ragnarsson, Binyamin Biraz Ouiz, Syntiya Strilka Vyrobnyk, Séamus Mac Padraig O Laoghaire) was swiftly augmented: in 1946 by the Srcetovredi Brothers Willie & Jack, and Részeg Vagyok; Jakov Redžinald (a former member of the BYO) around 1947; Zoya Căruțaș in February 1949; Chaya Malirolink and Etxaberri himself around 1950; the Ŭitmena Sisters in 1951; and Federica Rozhkov a/k/a Ferikarohasu some time before 1952.

This explosion of personnel recruitment—precipitated most probably by the social unrest, mobility, and economic uncertainty of Bassanda’s post-War reconstruction—led to a vast expanse in the ensemble’s expressive range and orchestral capacities, but also in its financial obligations. Nas1lsinez and Madame Szabo, the latter a particularly canny businesswoman, appear to have concluded that the only way to sustain the group’s sheer survival, as its payroll list expanded, was to diversify and formalize its relationship with the new Socialist regime put in place by the Soviet occupiers. BNRO historians suggest that this enhanced financial stability is the most plausible, if not the only, explanation why Yezget-Bey, a notoriously anti-authoritarian and anti-bureaucratic individual, might have agreed to submit to formal “State Ensemble” status.

In January 1967, he was not quite thirty-six years old.