New World a-Coming, Ch. 37

1951: Tommy Gassion, Howlin Wolf, and Mississippi Stokes at Sun Studios

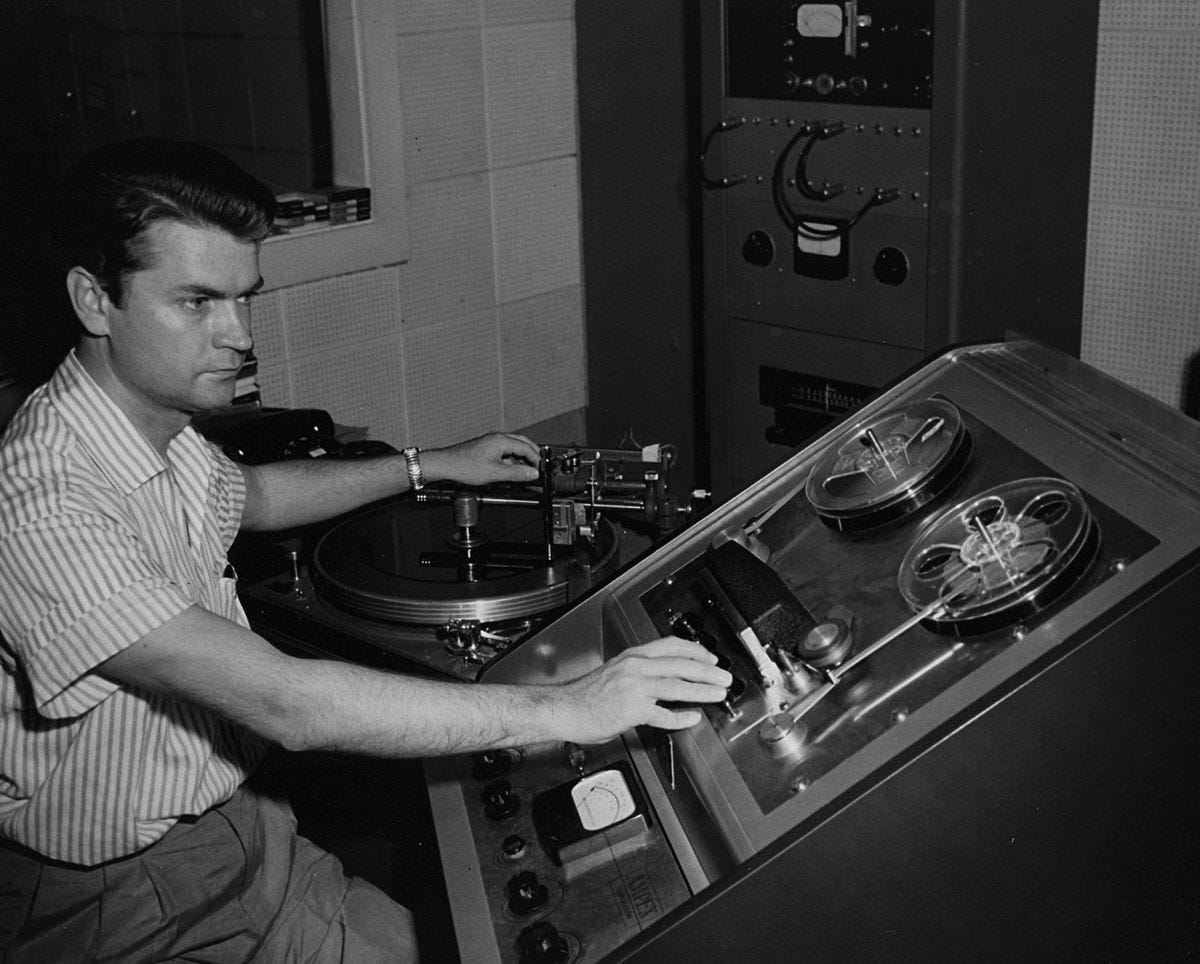

Sun Studios, Memphis Tennessee USA, 1951; from an unpublished memoir by Tommy Gassion, held by the Eagles Heart Sisters Oral History Project, authored circa 1955.

I was at the studio because I’d met Sam Phillips at some of the public events that he recorded and I covered. He was from around Muscle Shoals, and I knew that area, and so after I met him in Memphis, it led to me shooting a few of the artists that Sam was working with. I hadn’t placed any photos with the wire services, but he had interesting people coming in, and offering to shoot photos gave me an excuse to hang around the building at 706 Union.

Most of the musicians Sam cut demos on were black, so often times the only white folks there were Sam himself, and his secretary and business manager Marian Keisker—everybody else was black. That night, there was another person hanging out in the tiny control room. He was a skinny dude with that white hipster / bop cat look, although to be honest I don’t know if I would have made that association as early as the summer of ‘51, or whether the look came in later: dark hair slicked back, little mustache and soul patch under his lip, pegged trousers with pleats, a white dress shirt with the collar unbuttoned and the sleeves rolled up, a pack of Camels in the breast pocket, a pair of big tortoise shell-rimmed sunglasses like James Dean wore.

He was pretty unobtrusive; unlike some of those white boys who thought they were hipper to black music than everybody else, this fellow stayed in the background. But you didn’t get the sense he was shy--more just the idea that he understood why he was there and where the focus was and wasn’t. I got the sense—and not just because of the gray in his sideburns and soul patch—that he might have been older than he looked.

The Wolf actually is the one who brought him in; Wolf’ve been in before, with his band of Willie Johnson on guitar and Willie Steele on drums, and maybe this young white boy had been with him on one of those previous visits. I guess Ike Turner was there too, on piano so I understand, but when Wolf was in the room, you didn’t tend to notice anybody else tagging along: he was so much bigger than life, even though paradoxically he didn’t speak loudly at all: he’d stand close to you and listen attentively to what you said, and reply with a lot of thought. And despite what some said about him, you could talk to him and make suggestions about sound and he’d listen.

But when that red light went on, something else came out of him—every take he ever did that I ever saw he did it like it was the closing number of the last set at one of the juke joints back in Mississippi: on fire with the vocals, prancing around the room riding the mic stand like it was a horse, yelling at his players. Even if you’d never been in a juke joint, you still kind of felt like the Sun studio had turned into one, when Wolf was tracking.

So as I say this young white boy might have been in before, but if he had I didn’t notice him. This time was a little different however: Willie was having a little trouble with his guitar, and Wolf told the white boy, “Yo, Stokes, can you do something about that? Can you give it that sound you were getting before, with mine?”

The white boy nodded, and he took the guitar from Willie--it was an old Kay that was really beat up and I remember Sam wasn’t crazy about it because the pickups buzzed really loud, although noise was never something that Sam let get in the way of the performance. But the fact that the guitar was buzzing a lot and bothering Wolf mattered a lot; what Sam cared about with any of his artists was getting them to where they felt like the energy was right for them to do whatever it was they did. That could be tricky in the studio but Sam went out of his way there too to make it feel comfortable and safe. You wouldn’t think that Wolf was somebody who needed anybody else to make him feel safe—6 foot three and 230 pounds, with a sharecroppers hands—but he was actually pretty sensitive, and he’d be distressed if he felt like people weren’t helping him do his thing.

Anyway, the white boy appeared to get that, because he nodded and took Willie’s guitar, and went and sat in one of the straight chairs along the long side of the studio room, up against the acoustical tiles that Sam had laid in, and he put the guitar down across his lap, and he took a little zippered bag of tools out of his hip pocket. Sam said to the band, “Hey fellas, why don’t you come on out and take a smoke break and we’ll let this man do whatever it is he’s doing.” So the band filed out--they could have smoked in the control room, we all did but it was too small, so they went out to the front of the building. Ordinarily, almost a mile away from Beale Street, blacks might have felt uncomfortable about standing outside a building late at night, because the Memphis cops could be tough about the de facto curfew. But Sam was already well known as a radioman in town, and the cops had already gotten used to the idea that all kinds of people might congregate around the Sun building at all kinds of hours, and mostly nobody got rousted.

I was curious though, so I stayed in the corner of the control room, just kind of peeking out through the double glass window to the studio floor. Wolf had opened the back door that went out to the alley and there was a little bit of a breeze blowing through since they had opened the control room door too--we were glad of that, because it sure got close in there, late at night when we were cutting.

I watched the white boy and I saw him unscrew the pickguard from Willie’s guitar and then he loosened the strings a little bit, and I saw him sneak his screwdrivers in to take out the bridge pickup. Ordinarily I would never have messed with that, but Sam was a pretty good electrician and an old radio hand, and I had learned from him how to recognize somebody who knew what he was doing.

This white boy did. I saw him take out the pickup, and turn it over, and blow some dust out from between the magnetic pole pieces. But then he shook his head entirely and he got up and came into the control room. He leaned against the door jamb and said to Sam, “Borrow a soldering iron?” Sam pointed to the box of tools in one of his steel army surplus cabinets in the corner of the control room.

And then I have to admit I got a little bit nervous: even if Willie was too deferential—or too drunk—to get pissed off at somebody messing with his guitar, I’d seen Wolf lose his temper worse for smaller infractions. But I looked over in the other corner of the room, and Wolf was just leaning against the alley door, one shoulder, and watching this white boy work.

He unsoldered the power-points of the pickup. Then, with it entirely free from the guitar, he looked closely at the pole pieces: bringing them right up to his face but keeping his sunglasses on. Then he shook his head and dropped it on the floor next to him, underneath his folding chair.

And then he took off the sunglasses, and he looked up and directly across the little studio at me; I was surprised by the intensity his hazel eyes. Without even having been introduced, he said, “You got something for me?” Although I was taken aback, I nodded, and took the General’s package out of my pocket, and stepped down the few stairs into the studio, and handed it to him. It was wrapped in brown paper and strapped up with shipping tape, and on the package was just written the one word, “Stokes.”

I couldn’t see it very clearly, but I could tell by the way he handled it that it weighed more—almost as if the magnets were bigger, or heavier, or made out of something other than ferrous metal. He tapped the pickup points into shape and re-soldered its leads that went into the guts of the guitar. And he dropped it back into its well and screwed down the brackets. Wolf looked up and through the glass and gestured to Sam and Sam turned to me and said, “Go tell the band to get back in here; we’re ready to go.”

By the time the boys had got back into the room, the white fellow had tuned up Willie’s guitar and handed it to him. You could tell that Willie trusted him too, maybe because Wolf did.

They took their spots again; Willie plugged in his guitar to the house amp that Sam liked everybody to use—a big old Supro which Sam himself had hotwired out of a movie theater’s surplus speaker cabinet—and flip the switch. This time, there was almost no amp noise at all, but with the red light on the amp’s face glowing, it almost felt like the ions in the studio, and even through the double glass in the control room, suddenly got charged: like just before or just after a really close lightning strike in a summer thunderstorm.

The white boy looked at Willie, and Willie grinned and nodded. Then he turned and looked toward Wolf, who was in front of the band standing up at the straight mic stand with his harmonica. Even through the control room window and even though the white boy still had the sunglasses on, I could see him raise one interrogative eyebrow. Wolf grinned, and he said—louder than he usually spoke—"that’s how we do it in Mississippi. Good job, Brother Stokes.”

The white boy gave him a thumbs up and a nod, and this time he came out of the studio, and into the control room, and sat down on the corner, and fished out a cigarette without taking the pack from his pocket. Sam flicked his eye at me, and I got up and went over to this man Stokes and offered him a light. He took it, drawing the unfiltered Camel’s smoke into his lungs, and nodded his thanks.

Sam was looking through the double glass toward Wolf and the band, and he kept his eyes on them even as he spoke to the white boy. “So I understand from the Wolf that you are from Mississippi too, Mr Stokes. that right?”

The white boy took another drag on the Camel and then finally he took off his sunglasses and folded them into his breast pocket. His eyes were a surprising bright blue. He was expressionless, but then after a moment, as Sam finally swiveled in his studio chair to look at him—and Sam had a hell of stare—he smiled, and said,

“Call me Mississippi.”

And behind us, through the big control room monitors that Sam liked to use, we heard the Wolf began to sing.