The Great Train Ride for Bassanda - Ch. 13

Going to See the Professor

[Cécile Lapin speaks: the period is September 1906]

I went to see the professor in his cluttered study at the Sorbonne, bearing, as talisman or diplomatic offering, the copy of the 1874 Mystics, Musicians, Warriors, And Dancers Of High Bassanda from the Colonel’s shelves. As the General said “Don’t reckon it’ll tip the balance of his decision, either way. But it might pique his curiosity, just enough.” I also had with me, as further balm for the scholarly mind: a map; a calendar; a list of archaeological sites and a second map of ethnic language groups reasonably to be expected along the route; and a list of timetables for the newly-completed Trans-Caspian Railway.

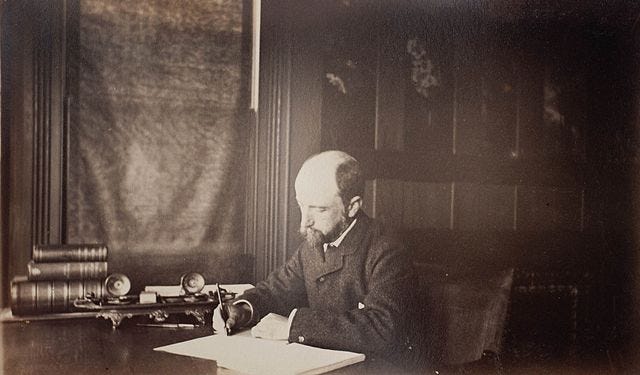

I sat in the visitor’s chair—how well I knew that chair’s hard seat and knobby wicker back, from our thesis meetings—across from his teak desk and explained the situation—quite convolutedly, I fear, as so much had happened so quickly. Meantime he sat watching my face, absent-mindedly (or so I thought) handling the loop of prayer-beads (mala) which he habitually carried; I had never had the temerity ask why or from where they were part of his life, but they were never far from his person. He was sufficiently attentive, considering his more usual vagary, but I was surprised, and not a little piqued, to discover that the Professor already knew far more about Bassanda, and even about my friends the Brethren, the General, Colonel Torres, and Main-Smith, than I could ever have imagined or than he had ever previously mentioned.

“Yes, yes, yes, Colonel Torres and the General I have corresponded with, and Madame Main-Smith and I have long family connections. I’m aware of the past history of the Russians in Bassanda, yes, as is any competent scholar of the East. Yes, yes, what of all that?!?”

I explained further, detailing the events of the alleyway attack, at which the Professor appeared rather taken aback. For a moment, he lost his scowl of impatience and listened in silence, and when he did speak, it was in a much more slow and thoughtful fashion.

“So…they believe that – the Russians know you are involved: that you are at risk?”

At the time, I felt only a certain vindication that he should be forced to confront the most recent aspects of the situation—here was at least one part of the story he hadn’t yet heard!—but looking back from the vantage point of years I now believe that, despite his typical irascibility, he was concerned about the risk to my well-being. Though he was not a conventionally sentimental man, and could be brusque and indeed dismissive to those whose intellectual capacities he found wanting, and he was—for an academic—quite egalitarian about both physical labor and physical risk for both sexes, in the wild parts of the world, there was a streak of the paternal in the Professor. Though I never felt he sought to intrude upon my personal life, or otherwise to usurp the role of father figure in the wake of my own parent’s premature decease, I came to understand that, despite his perpetual correctness, he did harbor protective feelings for me. These feelings were to have unforeseen and traumatic cost in the months ahead, though such could not be anticipated at the time.

The night before, there had been little speculation about Russian motives or tactics; as the General had said, in his characteristic laconic fashion, “Doesn’t matter what they intended for you; can’t tell for sure, and there ain’t a one left to testify. Only way to find out, now, is to go.” We had, however, come to the conclusion that I would travel under a different name—if “Cécile Lapin“ were a target, and if it was the Professor’s name and fame that was needed to open doors and frontiers rather than any of mine, then it were safer for me alias utens.

Under further cross-examination, I expressed the Brethren’s own unclarity on his latter question: did the Okhrana know of my involvement, before I myself did? Or were they simply seeking to permanently silence the Colonel and General, given opportunity in the night streets of Paris—that is, was it simply an attempted assassination-of-opportunity, with myself as bystander? Had I then been altogether mistaken about the thugs’ intent to kidnap me? I felt at a loss, and in truth rather stupidly unprepared, due to my inability to answer any of his questions.

Finally, feeling frustrated and inadequate, I took from my handbag a brown-paper parcel which contained the Colonel’s gift of Warriors, Mystics, Musicians, And Dancers of High Bassanda and handed it across the Professor’s desk.

“Sir, the Brethren believe that your cousin Habjar-Lawrence Nas1lsinez may have discovered the lost Documents—that he may have been the one who brought them out of Bassanda decades ago and, by many a wandering road, to Paris. The Colonel bids you turn to the bookmark within this text.”

He put down his prayer beads upon the desk’s blotter and took the parcel from me slowly; I almost got the sense that he knew the volume’s before he began unwrapping it. Having set aside the brown paper, he held the book in his hands, turning it over and over, before finally opening the cover and reading the title page.

“I’ve never seen this—the first edition is so rare—but I have heard about it. The notorious Cousin Habjar. I never met him—few in the family even spoke of him. My grandfather’s elder brother’s son and something of a black sheep; he left school and went East…and a lot of that side of the family’s fortune went with him. Sold off the Throbshire estates, repudiated the west, but…still…I don’t know that he was a black sheep, so much as an adventurer. And those adventures always seemed to lead East.”

He ran a finger down the table of contents, and then turned to the last pages, searching for the nonexistent index. Finally, and with seeming reluctance, he let the volume fall open to the bookmark. Peering through his spectacles, he read silently for a moment; then stopped and looked up at me, expressionless.

Then he turned back the page, and began to read again, aloud this time, following the text with his finger.

“In the year of the Prophet 1036, it is said that, when the Turks came to the frontiers of Bassanda, seeking to enslave the free People and take our land, the Iliot shamans came with teachings from the ancient chronicles. These were drawings and from them were built mighty Machines which gave great strength at a distance to resist the Oppressors. With them, the free People were able to repel the Turks and defend our Mother.”

He looked up and met my eyes. “But I must admit that this text has the feel of others whose authenticity I can confirm. The sense of historical crisis in this text is persuasive.”

He paused for a moment.

“As much, I must acknowledge, as it is in the account of your recent encounters.”

And so, in the end, he reluctantly agreed to meet with my three Friends.