[Lapin’s account, Spring 1907]

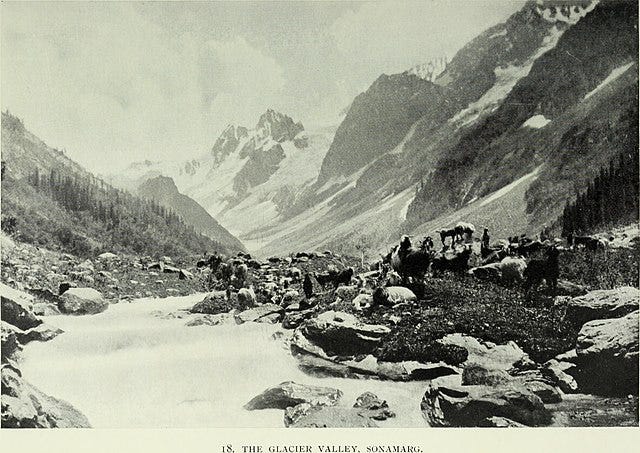

We had been riding, in near-whiteout conditions, since early morning. Though the sun had crossed overhead as we rode north, myself and the Khampas, across the slopes of the Three Brothers, the blizzard blinded us in the swirling snow that seemed like dusk. I sat my pony, content to let him follow the slow single line of riders led by Arbō’s Parva guides. I thought back to the night before.

As we sat at a front table in the Great Room of the Matthiaskloster, Winesap had objected, adamantly, to my leading a second search party to supplement the Colonel’s own. While he was admirably free of the domineering conduct of entirely too many men of my own generation—perhaps because he came from a later one—he pleaded with me to reconsider. His voice was shaking.

“Mademoiselle Cécile: if there must be an additional search party, I beg you to allow me to serve as liaison. I know you think I’m a bookworm—but before I was a librarian, I did my time walking point in the jungle. And I am far less essential to the cause of Bassanda than are you. Please allow me to take on this risk in order to assure your safety.”

He paused, and in his face was torment.

“Mademoiselle, I… I feared that Ismail might be lost. In my work at the Archive, in that time in the future, I had read the accounts of his heroism, and… those future accounts… they contradict one another. Some recount his later life, and his heroism in other wars, but—others—”

He swallowed convulsively. “Other accounts say that…he died. Or, he disappears from the chronicle. I had hoped, desperately, hoped against hope, that those future accounts might be mistaken—that I myself might be. And so I said nothing—because…I know the pain of loved ones’ violent death.”

[marginalia, in Winesap’s hand]

My father and my elder brother were killed by Klansmen in north Alabama in ‘55, when I was eight. I’ve never forgiven myself.

[Lapin]

Winesap’s dark, sensitive face had been alive with passion as he pleaded. I clasped his arm gently; it is perhaps a measure of the trust that already existed between us that he, who with his combat fatigue hated to be held, submitted to this touch without argument. He made to continue but I gently shushed him.

“My dearest friend, I swear to you that I am not seeking martyrdom, not even for my beloved Ismail who has died. Do not forget that, like yourself, I too was brought up with hunting—and killing, when necessary. I too have lost friends and family in the defense of freedom, before this. I have no heart left to break. And you have the expertise to assist the General in the realization of the one Device that might help us, outnumbered as we are, tip the balance in the coming battle.

“I fight for my lost ones, Jefferson, just as you do. This will not be the first time that karma has demanded of us that we battle onward in the absence of hope.”

He had remained silent, staring at the old oak tabletop between us. Finally he sighed and looked up. There was a force and a clarity in his dark eyes, and a slow-burning fire behind them, that I had never seen before.

“Very well, Mademoiselle. As you say, so it shall be. But if the end comes, look for me there, then, as well.”

I had embraced him and kissed his cheek. “Very well, Samuel. Each to his own task, then.”

But in fact I had been lying to him. Tenzing Badr had insisted that the nightmare of seeing death through Ismail’s eyes could not be discounted as a fiction, adding only, “It is folly to think that one can use the Eagles’ Vision to see one’s own future: one can only see, in real time, the present moment, through the eyes of those with whom one has held a karmic connection. That connection can be one of love, or of anger, or death itself.” He would say no more, insisting that he could not see any further than I had, to that moment when my sight-through-Ismail’s-eyes had swirled into reddish blackness.

I believed he had died. I wanted to die.

But I had not wept. I would not weep.

I shivered and came back to the present. The Khampas moved through the swirling snow nearly as silently as the night wind, hunched in the saddle, reins loose to allow their mounts to pick the path, and so at one with their steeds that the little ponies themselves maintained the same disciplined silence. We were following the beaten-down path of the raiding party, a dozen yards wide but already being covered by drifting snow. There were drops of dried blood, black against the snowy path.

On foot at the head of our double column of riders, the Parva leader Arbō, with one hand on Lhakpa’s stirrup, stepped lightly along the track, bent nearly double as he followed the raiders’ spoor. At intervals, he would tug on the stirrup, and Lhakpa would halt the column in order to lean down and confer in muttering voices with the Parva.

From up ahead, there was a tiny whistle, barely audible through the sound of the blizzard’s shifting winds. The Khampas drew rein, still maintaining noise discipline. The Parva Jingmo appeared at my stirrup, dark and hairy against the whiteout snow, and gestured that I and my riding companions should dismount. We slipped from the saddle, each pausing to tie a burlap bag across the halter to muffle the sound of his pony’s snorting. We laagered our steeds in a small tight circle, gently pressing on a near-side shoulder until each lay on its belly. The snow immediately began drifting over the ponies’ backs and hindquarters: within just a couple of minutes, the circle had already begun to take on the coloration and blurred appearance of drifting snow.

I was crouched between my own pony and Lhakpa’s when Arbō appeared out of the white-flaked dark, like a spirit of the storm: he had another of his Parva scouts with him. They squatted next to us, the scout whispering in Arbō’s ear, he in turn translating to Lhakpa, and Lhakpa to me:

“Jingmo says that the lowlanders from the north are ahead, a few hundred steps, up over the ridge and down the slope beyond. He says that you can smell their campfire.”

Arbō paused for a moment, as if reflecting, and then said directly to me, in slow and laborious Tibetan:

“What is the Daikini’s will?”

I replied, “Tell him that he has done well. Tell him our brother Lhakpa and I will go forward now. Thug de je, Jingmo.”

Arbō looked at me expressionlessly for a moment. But then he nodded, and with Jingmo slipped away into the night.

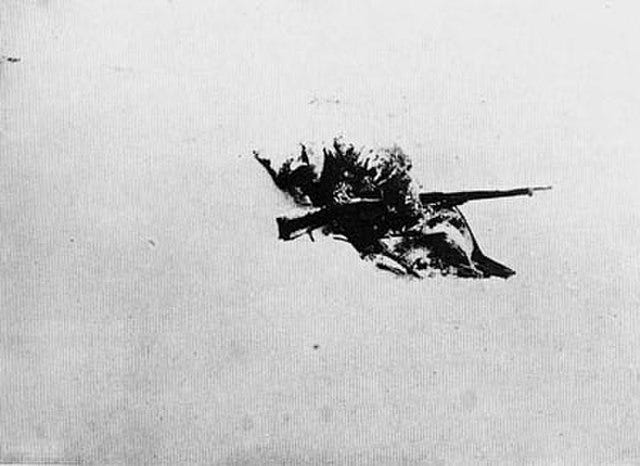

I looked at Lhakpa, whose eyes were wide with excitement: “We go now, Brother.” Moving at a crouch, we crept forward to the top of the ridge, whose edge was already marked by a crest of newly-drifted snow. Once on the other side, the wind dropped, and the snow was much lighter, but as a result the footing on the loose scree was much more treacherous; we dropped and began to crawl on all fours as the terrain sloped downward.

We had traveled like this for less than fifty meters when, peering ahead and downhill, I caught a momentary glimpse of the dancing spark of a distant campfire, before a fresh gust of snow blotted it out of sight. We stopped.

I motioned Lhakpa to hold his position. For a moment, he stared at me, but I will say this for the Khampas and Tibetans—they do not presume that a woman is incapable of deadly work. He nodded, reaching up to carefully and slowly unsling his rifle while remaining silent and prone. He brushed a bit of snow from the rear sight and eased the rifle forward, propped on his elbows and pointing down the darkened ravine to the raiders’ campfire. Then he looked at me and nodded; in the swirling darkness of the snowstorm, I saw his teeth flash as he grinned with excitement. He whispered “Rāmrō bhāgya, Simhamukha.” I nodded, touched the pommel of the Bowie fighting knife the Colonel had given me, and began the excruciatingly slow, silent crawl down-slope toward the campfire. I was shortly soaked and shivering, with my hands and elbows abraded by the rough wet scree, but I never even considered shifting my one-pointed attention on the tiny dancing flame that lay ahead and below.

The sentry was perched on a low boulder, rubbing his mittened hands, his rifle across his knees. No doubt because of the cold wind that whistled downhill from the ridge above, where Lhakpa and our Khampas lay in concealment, the sentry had gradually shifted his orientation, giving his back to the wind and huddling inside his sheepskin coat. His face was likewise turned to look downslope. I imagined him longing for the end of his watch and a chance to return to his comrades’ fire, thinking there could surely be no danger in this remote, icy-cold place…

Until I came silently out of the dark and killed him.

I crouched above the prone body for a moment, its legs still twitching, my left hand still over his mouth and my right wet with blood, staring downhill and listening for any alarms from below. I did not believe that there would be any such: no sound could have been audible from more than a few feet away. But I also knew that there was no time to lose.

Still watching the distant campfire below, listening intently for sounds that would indicate, against the odds, that the sentry’s relief might be climbing toward this post, I felt over his body for insignia or badges. Then I gently rolled him onto his back, feeling in the faint starlight for any such identifiers; there was a tag on a thin chain around his neck.

Then I looked at his face, and despite the adrenaline I could feel pumping through my veins, I froze for a moment. The features were Asiatic, not European, and those of a young man, barely more than a child. And I had killed him.

Who were these raiders?

But this was not the time or place for speculation. I yanked sharply on the medallion and its chain broke. Thrusting it inside my jacket, I rolled the body back onto its belly, scuffing up a few rocks to obscure its outline: I was worried that, with the moonlight reflecting on the snowfields above, others of the raiders might notice a change in the sentry’s silhouette. Then, with the only listener in earshot huddled lifeless, I ran in a crouch, my feet crunching in the powdery snow and loose scree, back up the slope to where Lhakpa waited, dropping down prone beside him. He hissed at me, raising his eyebrows in inquiry.

“Just one,” I whispered. “I cannot tell if they have our friends, but I did find this.”

He saw the blood on my hand as I held out the sentry’s identity medallion on my open palm. Taking it carefully between thumb and forefinger, he tilted its face toward the half-moon that was just rising over the mountain ridge to our southeast. I could not make out the insignia in the medallion’s center, but I recognized the characters in the inscription:

新军精英侦察部队[1]

I looked at Lhakpa and said,

“‘New Army Scouts’? The Chinese?”

Lhakpa nodded.

“Yes, Simhamukha. The Manchus from the east, as well as the Cossacks from the north. They make common cause against us.”

I was thinking hard, but Lhakpa’s urgent whisper interrupted me.

“Lady—was there no sign of the Professor? Or of Ismail Bhā’i?”

I could not answer. I did not know, as I had not dared enter the camp itself. But there came rushing back the fear and anger and terrible emptiness I had known when the Colonel gave me the news of my lover’s capture. My vision swam, and I seemed to see Madeleine Froissart’s smiling voice, alight with the mischievous joy in life, as I had last seen her alive, that day on the terrace of Lilas, months before and thousands of miles away. I saw, through Ismail’s eyes, the martyrdom of my beloved Professor. I saw Ismail’s own life-force flee as he fell forward into blackness, in my dream of just one day before. I felt the blood pounding in my ears and there was a red mist behind my eyes.

Lhakpa was watching me closely.

“Lady—we must get word to the Brethren. But we cannot leave such as these to report that two of our own remain taken. And we must be sure: we must discover if there is any other evidence of the whereabouts of Lawrence-Geshe and Ismail Bhā’I’; where or indeed if they are gone.”

I met his eyes. I knew the strategic inevitability of what came next.

“Lady, there is only one thing to do. They are camped, these Manchus, and the Cossacks have departed, perhaps with our friends. As yet they suspect nothing. It is dark, and we and the Parva are in our element. They do not know that we are on the hunt for them—but if they discover your quarry the sentry, they will know. We must assure that their masters do not know either. We can leave no trace.”

In that moment, in the red darkness of that rage, I knew what we must do. I felt my heart harden within my chest, as if it were contracting from the freezing cold.

I nodded.

“Then, Lhakpa, let us do what must be done.”

He looked at me and nodded, “So must it be, Daikini Manjushri.” We turned to slither back up the slope above the ravine to our ponies and find our Khampa comrades. Below us, the spark of the raiders’ campfire danced like the last guttering embers of a distant candle.

We killed them. All of them. Silently, in the last hours before dawn. One by one.

Later, in the ringing cold after the storm dropped, as the icy golden light of the sun began to spill over the snow-clad ridge to the east, we searched the bodies of those we had slain. And just beyond, across the camp from the slope where I had killed the first sentry, I found my beloved Professor Habjar-Lawrence’s poor broken body, shot full of holes, surrounded by the corpses of his Cossack foes.

And in the satchel of the hetman who had commanded the raiders—now splashed with his blood—I found the mala that I knew so well, that I had come to know on my lover’s wrist as we lay together on the Orient Express.

And in that moment, amongst the tangle of discarded saddlery and weapons, as the Khampas dragged Cossack and Manchu corpses together to bury them under piled rocks, as they tenderly wrapped the Professor’s body in a horsehair blanket, I remembered my nightmare, weeks ago in Paris, of Madeleine dead and bloody in the flat we had shared. I remembered the horror of that dream, and my terror, and hers. And that of the young Chinese conscript I had killed, and all the other innocents who had suffered and died. The vile red rage was gone. All that was left was revulsion.

I clasped that mala, the symbol of Ismail’s spiritual aspiration even when he had killed—even as I had now done myself—in the name of Bassanda, like the mala I remembered on the Professor’s desk at Paris, now half a world away. And I remembered the warning he had shared, about the irredeemable karma of violence.

And finally, I wept.

[1] Xīn jūn jīngyīng zhēnchá bùduì “New Army Elite Scouting force”