FRIDAY BONUS: Bassanda's contingent capacities for joy

Evelyn Nesbit, Cecíle Lapin, and the contingent alternate-historical possibilities—and obligations—of joy

BONUS POST 01.28.22

Sharp eyed observers, or those familiar with turn of the 20th century high society—and scandal—will recognize that the portraits of Cecile Lapin in THE GREAT TRAIN RIDE are, in fact, derived from public domain images of the artist’s model, dancer, society woman, and prototypical media star Evelyn Nesbit (1884/5-1916). The subject, in the 19-Oughts, of an enormous level of attention via paintings, photographs, and her involvement in one of several “Trials of the [New] Century,” she was most notoriously the subject of a love triangle between a rich white male rapist and a rich, white, and psychopathic husband who abused Evelyn, murdered the rapist—and still walked.

From rural Pennsylvania and the child of a penniless single mother, in her teens Nesbit was widely photographed and painted as either an exotic or an ethereal presence by JC Beckwith, FS Church, and, most famously, Charles Dana Gibson, the model for the latter’s famous illustrations of the idealized Edwardian “Gibson Girl.”

Her nearly-penniless mother, who served in some periods as her manager, insisted that she never let Nesbit post “in the altogether,” but from a 21st century perspective, the numerous period photographs and lush oil paintings of a semi-nude teenager are deeply disturbing.

Seeking career alternatives by entering Broadway theatre in 1901 as a chorus line dancer, she quickly became a favorite of wealthy men-about-town, most two or more decades her senior, though she also kept company, more willingly, with her nearer-in-age contemporary, the youthful John Barrymore, who loved her for the next 35 years.

In 1905, when Evelyn was no more than 20, she married the drug-addicted millionaire Harry Thaw; a year later, in a shocking public assault, during a performance of Mam’zelle Champagne Thaw shot and killed Stanford White, who he alleged had raped Evelyn while she was unconscious. After not one but two “Trials of the Century,” the Thaw family’s wealth, and their manipulation of the press, elicited a verdict for Harry of “not guilty by reason of insanity.” His “confinement” to the Matteawan State Hospital amounted to little more than house arrest; he subsequently fled to Canada, and upon return was absolved of all penalties, though Nesbit was finally able to divorce him in 1915. Traveling the rough circuits of international theatres, cinemas, and nightclubs, her 1920s and ‘30s experience was marred by alcoholism, controversy, and a continued and deeply dysfunctional relationship with the murderous and abusive Thaw—who finally died in 1947.

Nesbit later relocated to California, and took classes in sculpting and ceramics, eventually teaching at the Grant Beach School of Arts and Crafts. She died in Santa Monica in 1967.

Her early autobiography was published as Tragic Beauty: The Lost 1914 Memoirs of Evelyn Nesbit, but perhaps the best-known and most empathetic portrait is in E. L. Doctorow’s retconned historical novel Ragtime (1975), itself a significant model for the Chronicles of Bassanda, wherein Nesbit and the anarchist firebrand Emma Goldman make common cause. She was portrayed by Elizabeth McGovern in Miloš Forman’s film version, where her most moving interactions are with the immigrant “Tateh,” played by Mandy Patinkin—a character and an actor who are both, by all accounts, every kind of gentle, ethical, honorable man that the real Nesbit never knew.

Evelyn was a stunningly beautiful woman but an unnervingly beautiful child—unnervingly, because one can sense the creepy exploitative intentions behind the lens and the easel. We can all think of later iterations, in our media culture, of the sexualization of childhood by patriarchy, and they rightly appall us.

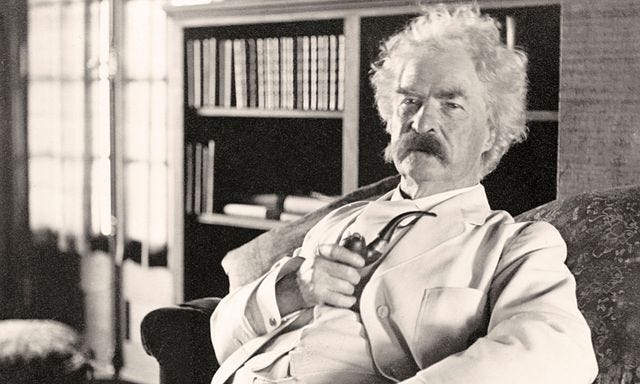

The acid-tongued Mark Twain, for example, had no illusions about the greed, selfishness, and violence of Thaw, or White, or any of the other rich oligarchs upon whose molecule-thin pretensions to “class” he bestowed the epithet “The Gilded Age. One needn’t even wonder what Mr Clemens would have thought of the gold toilets and bronzer of the sociopathic child-raping grifter who was POTUS 45, because Twain talked about the abuse of Evelyn Nesbit.1

So by what right do we bootleg these (admittedly public domain) images of poor, beautiful, abused Evelyn Nesbit, to serve as iconic representations of the Bassandan heroine Cecile Lapin? In truth, the imagined character of Cecile came first—this Norman-born, peasant-raised, self-educated Sorbonne graduate student; comrade of the Colonel, the General, and Madame Algeria; lover of Ismail Durang: a Bassandan freedom fighter and the heroine of THE GREAT TRAIN RIDE—

—and then, when we went looking for visuals, mostly as an aid to creative imagining, Evelyn appeared.

Yes, these images are public domain, appearing on Wikimedia Commons and ubiquitously across the copyright-gray Internet—but the fact they are “copyright free” does not mean we have the right simply to hijack Evelyn’s image, shed of her back-story or indeed of her own agency, or to bend it to our narrative, unless we acknowledge the karmic debt such use carries.

But in one particular portrait from 1905, Nesbit stares, long dark hair tousled and her white shift half off one shoulder, directly into the camera—and the power and directness of that gaze, that sense that this 20-year-old’s eyes have seen things no child should see, conveys some sense of the steely courage and dogged willingness to give love, even after heartbreak, that we sought to find within the contingent tale of Cecile Lapin, Ismail Durang, and the Cause of Bassanda. This Nesbit is the woman who fought for herself, for her son by Thaw, and for the opportunity, armed against the world that would have consumed her beauty, abused her person, and cast her aside, to determine her own fate.

So what are the ethics of historical contingency? How do we acknowledge the karmic debt, and maybe even put some better karma out into the world, on behalf of Evelyn Nesbit and of all others who might suffer similarly, in either fiction or history?

In his novel Dune, set in a millennial future across an ecosystem and feudal infrastructure of hundreds of planets, the visionary polymath Frank Herbert establishes a new set of moral ethics in a post-technological world from which computers are banned, including the commandment (from his “Orange Catholic Bible,” compiled from ecumenical sources including the “Maometh Saari,” “Mahayana Christianity,” “Zensunni Catholicism,” and “Budislamic” traditions, after the Butlerian Jihad which had destroyed and condemned technology):

“Thou shalt not disfigure the soul.”

It is likewise a core spiritual value in the world of Bassanda.

Bassandan ethical teachings—and those of the historian—extend the commandment even further,

“Thou shalt not disfigure the past.”

In the case of Evelyn Nesbit/Cecile Lapin as an actress in the story of the Great Train, this means we are commanded to honor her story through the agency of our telling: its pain, its loss, and its potential. Employ no images, visual or textual, which exploit her childhood; seek instead imagery that conveys an adult woman’s joy, strength, and agency. Build a narrative which celebrates both the best of Evelyn as she was and those parts of Evelyn which could have been, had her circumstances been better. Give her agency and acknowledge her heroism. Make hers—with that of S. Jefferson Winesap, another traumatized and minoritized invented character—the main narrative voice. Allow Cecile an arc of sadness, loss, suffering, but also of defiance, and the transcendence of suffering through courage—as we would, if we could change the history of the past, do for Evelyn Nesbit as well.

We can no longer change the circumstances of Evelyn Nesbit’s life. But we can perhaps provide a contingent alternate narrative, an imagined history of that life, as “Cecile Lapin,” which finds heroism, joy, and cathartic transformation.

The body of sutra (sacred texts) associated with our universe’s ancient Iliot shamanic tradition, infused with Buddhism and primitive Christianity as was Herbert’s O.C. Catholic Bible, provides the following, which shapes the imagined world of Bassanda, its own alternate and imagined histories, biographies, and ethics. We dedicate and rededicate ourselves to the moral rigor of this commandment from the Bassandayana, on behalf of Cecile Lapin, Evelyn Nesbit, and of the contingent stories of joy we will give them:

“Thou shalt not disfigure the future.”

TWAIN, MARK. “1907: Autobiographical Dictations, March–December.” In Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 3: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, edited by BENJAMIN GRIFFIN, HARRIET ELINOR SMITH, Victor Fischer, Michael B. Frank, Amanda Gagel, Sharon K. Goetz, Leslie Diane Myrick, and Christopher M. Ohge, 1st ed., 3–195. University of California Press, 2015. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv1xxtgh.5.